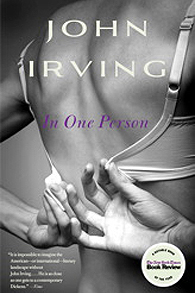

John Irving: Author Q & A

You can download this Q & A in a print/mobile friendly PDF here.

The protagonist and first person narrator of In One Person, Billy Abbott, is bisexual. Why do you think bisexuals are rarely represented in literature?

The bisexual men I have known were not shy, nor were they “conflicted.” (This is also true of the bisexual men I know now.) I would say, too, that both my oldest and youngest bisexual male friends are among the most confident men I have ever known. Yet bisexual men—of my generation, especially—were generally distrusted. Their gay male friends thought of them as gay guys who were hedging their bets, or holding back—or keeping a part of themselves in the closet. To most straight men, the only part of a bisexual man that registers is the gay part; to many straight women, a bi guy is doubly untrustworthy—he could leave you for another woman or for a guy! The bisexual occupies what Edmund White calls “the interstitial—whatever lies between two familiar opposites.” I can’t speculate on why other writers may choose to eschew the bisexual as a potential main character—especially as a point-of-view character (Billy Abbott is an outspoken first-person narrator). I just know that sexual misfits have always appealed to me; writers are outsiders—at least we’re supposed to be “detached.” Well, I find sexual outsiders especially engaging. There is the gay brother in The Hotel New Hampshire; there are the gay twins (separated at birth) in A Son of the Circus; there are transsexual characters in The World According to Garp and in A Son of the Circus, and now again (this time, much more developed as characters) in In One Person. I like these people; they attract me, and I fear for their safety—I worry about who might hate them and wish them harm.

Great Expectations has an enormous influence on Billy in more than one respect. What are some of the books that helped to define and influence you at a young age?

Like Billy, I spent some of my childhood backstage in a small-town theatre; my mother, who—in many respects—was not like Billy’s mother, was a prompter in a small-town theatre. My earliest interest in storytelling came from the theatre, and I imagined myself as an actor (onstage, never in the movies) before I imagined being a novelist. But Great Expectations, and other novels by Dickens, inspired me to want to write those plotted, character-driven novels of the 19th century—also Hardy, Melville, Hawthorne; also Flaubert and Mann and the Russian writers. But before I was old enough to appreciate those novels, I saw Shakespeare and Sophocles onstage; those plays have plots. There were plots in the theatre—centuries before the earliest novels were written.

You do a magnificent job portraying the AIDS crisis in New York in this novel. Was it difficult for you to encapsulate this moment in history?

If you mean “difficult” in terms of research, no. Other novels have been much harder, in terms of research—in terms of having to teach myself about something foreign to me—than In One Person. But, yes, it was difficult—personally. I lived in New York City from ‘81 till ‘86; I was there at the start of the AIDS crisis, I lost friends (young and old) to that disease. I had no desire to revisit some of those memories. But I have two good friends (and fellow writers) who I knew would be reading this manuscript—over my shoulder, so to speak. I doubt I would have begun writing In One Person if I didn’t know I could count on these two friends as essential readers: Edmund White and Abraham Verghese. I knew if I made a mistake, they would catch it; I have complete faith in their authority. They gave me confidence; they allowed me to write freely—they were my safety nets.

In One Person features some of the classic signatures that your readers have come to expect to find in your books: wrestling, living abroad in Vienna, the loss of childhood innocence, an absent parent, New England boarding schools, sexual deviants, etc. What is it that attracts you to these themes and settings again and again?

Ah, well—there are the subjects for fiction or the “themes” you choose, and then there are the obsessions that choose you. Wrestling is something I know: I competed as a wrestler for twenty years; I coached the sport till I was forty-seven. The life in a New England boarding school, and living as a student abroad in Vienna—these are simply things I know very well. I choose them because I have no end of detail in my memory bank, regarding those oh-so-familiar things. But “the loss of childhood innocence,” or “the absent parent,” and those sexual outsiders and/or misfits I am repeatedly attracted to in my fiction—well, I do not choose to write about those things. Those things obsess me; those things choose me. You don’t get to pick the nightmare that wakes you up at 4 A.M., do you? That nightmare comes looking for you, again and again.

What was behind your choice to make libraries such an important part of Billy Abbott’s development?

I love libraries. I used to read in libraries, write in libraries, hide in libraries; libraries embrace a code of silence—that was just fine with me. I went to libraries to be left alone. So much of being a writer is seeking to be alone—actually, needing to be alone. Bookstores aren’t the same; they’re social places. I was a fairly antisocial kid; libraries were my cave.

Was your experience with writing In One Person different from your other books? If so, how? Did you write the last sentence first, as you’re famous for doing?

No, not different—very much the same. I always begin with endings, with last sentences—usually more than a single last sentence, often a last paragraph (or two). I compose an ending and write toward it, as if the ending were a piece of music I can hear—however many years ahead of me it is waiting. The ending to In One Person is a refrain—the repetition of something Miss Frost says to Billy, which Billy repeats to Kittredge’s angry son. It’s a dialogue ending. I’ve done it before: in The Cider House Rules, there is the repetition of the benediction the old doctor used to say to the orphans at the end of the day—that echo of the “Princes of Maine, Kings of New England” refrain, like a repeated stanza in a hymn. There is also the echo in A Widow for One Year, what Marion repeats to her daughter at the end of the novel. (“Don’t cry, honey. It’s just Eddie and me.”) Well, Billy Abbott repeats Miss Frost’s command, her “My dear boy” speech, at the end of In One Person; that’s another so-called refrain ending—the reader is taken back to the first time those words were used. They have to be words the reader will remember!

In One Person is your thirteenth novel. Do you have a favorite John Irving novel?

I have three children; I don’t have a favorite child. You love them all. But, of my novels, I say this: The last eight, beginning with my sixth novel (The Cider House Rules), are better made—better constructed, better written—than the first five. I know why. I didn’t become a full-time writer until after The World According to Garp (my fourth novel) was published; I didn’t teach myself how to write for eight or nine hours a day until after I’d written The Hotel New Hampshire (my fifth novel). There’s a difference between writing all the time and being able to write only some of the time.

This book focuses on the topic of tolerance, especially of the LGBT community, over a time span ranging from the late 1950s to the present day. What made you want to write about such a hotly debated topic?

I think that “want” isn’t the right word; maybe the feeling that I “have to,” or that I “should,” write a certain story is what drove me in this case. When I finished The World According to Garp, in the late seventies, I was relieved; that was an angry novel, and the subject of intolerance toward sexual differences upset me. Garp is a radical novel—in a political and violent sense. A man is killed by a woman who hates men; his mother is murdered by a man who hates women. Sexual assassination was a harsh view of the so-called sexual liberation of the sixties; I was saying, “So why do people of different sexual persuasions still hate one another?” Well, I thought I would never revisit that subject. In One Person isn’t as radical a novel as Garp; it is a more personal experience—I made Billy a first-person narrator to make the story more personal. But Billy is a solitary man. “We are formed by what we desire,” he says—first chapter, first paragraph. Later—over 300 pages into Billy’s story—he says, “I knew that no one person could rescue me from wanting to have sex with men and women.” He’s not complaining; he’s just stating a fact. I can’t accept that gay rights, or the rights for people who are bi—or the rights for transgender people—are as “hotly debated” as you say. I think the “other side,” those people who can’t accept sexual identity as a civil rights issue, are moral and political dinosaurs. Their resistance to sexual tolerance is dying; those people who are sexually intolerant are dying out—they just don’t know it yet.

Over the years, you’ve coined certain phrases that have become very popular with your readers: “Watch out for the undertoad,” “Sorrow floats,” “Keep passing the open windows,” “Good night, you princes of Maine—you kings of New England,” etc. You continue this tradition in In One Person when you write about “Crushes on the wrong people.” How do you come up with these sayings? Do you ever find yourself saying them?

Well, there’s a line early in In One Person, a line like that. “All children learn to speak in codes.” And there’s the repetition of Miss Frost’s command to Billy, her “My dear boy” speech, which reappears at the end of the novel. (“Don’t put a label on me—don’t make me a category …” I mean that speech.) There are always these phrases that serve as refrains, or choruses, in my novels; they have to be something you, the reader, will remember. Naturally, they reverberate with me; I can’t forget them. Think of the role of the Chorus in those Greek plays, or what the Fools or the Clowns (or the Witches) say in Shakespeare’s plays: these characters don’t merely describe what has happened; they foreshadow — they are prophets of what lies ahead. I love those lines of foreboding; there’s a sentence of that kind on page 16 of In One Person, the one that goes “Oh, the winds of change; they do not blow gently into the small towns of northern New England.” We are many pages away from seeing how Miss Frost will be judged, but there’s a warning.

Do you have another book in the works? If so, can you provide a sneak peek of what it’s about?

I feel fortunate that I always have to choose among two or three ideas; I usually have as many as two or three (or four) novels “waiting” to be the next one. Sometimes these novels have been waiting for many years. I don’t always choose the one that has been in the back of mind the longest. The choice often is made on the evidence of how much I know about the ending — how clearly, or not, I see the end of the novel. In One Person was in my mind for six or seven years (or more) before I began writing it in the summer of 2009; in June of 2009, I would not have guessed that In One Person would be the next one—I just suddenly saw the ending, and with it the whole story. I wrote this novel very quickly for me—only two years. But there was little research—there is often much more research—and these characters and the trajectory of their story have been known to me for almost a decade. As for right now, I am thinking of four ideas, but I haven’t chosen one: a ghost story, a miracle story, a love story, an adoption story.